This article is sourced from the archives of the Inishowen Maritime Museum, Greencastle, Co. Donegal

Pilotage in the Foyle

Marine Pilotage is one of the oldest professions in the world, with references to pilots to be found in some of the earliest recorded history. For as long as ships have been sailing the seas, there have been maritime pilots to assist them in the approaches to ports, the most treacherous part of their passages.

A maritime pilot is now defined as a seafarer, not part of the ship’s crew, who has detailed knowledge of a port approach, or dangerous navigational area, expertise in ship manoeuvring and uses that knowledge to ensure the safe passage of a vessel within a specified area.

Before harbour authorities were established, pilots known as “hobblers”, or “jumpers”, would compete with one another to reach an incoming ship to negotiate with her captain to pilot the ship into the docks and receive payment for the work.

Some sailing ship companies began to “retain” pilots to service their vessels on regular routes.

Regulations were introduced around the coast so that the Harbour Authority in each area examined sailors to be pilots and licensed them to perform the relevant pilotage duties within the Authority’s area of control.

Pilots, and the boatmen who took them to and from the ship, were paid by the ship’s owner either directly by the ship’s master or through the ship’s agent.

Pilotage Fees were set by the local Harbour Authority. In many cases the collection of pilotage fees was done by the harbour authority, along with other harbour dues, and the pilotage fee was managed and disbursed by the authority.

In the days of sailing ships, when a ship had no cargo, she had to carry enough ballast to maintain her stability and to prevent her being rolled over by the wind in her sails. This ballast was shipped. or discharged, in the port visited.

The “Ballast Office” in each port collected the charges for loading, or unloading, ballast, so the recording of this ballast amount was developed into a method of creating a tax on each ship for her use of the port’s services.

Later all these consolidated charges became the responsibility of the harbour authority and were generally referred to as harbour dues.

It was the responsibility of the harbour authority to maintain a list of sufficient licensed pilots to cater for the trade into the port, so the number of licensed pilots varied as trade into the port changed.

Harbour dues and service fees were set by a local committee within the port authority, made up of merchants and port users, known as the Ballast Committee, Ballast Board or Ballast Office.

A Ballast Board was established In Dublin, in 1786. The Ballast Committee in Derry was established in 1845.

The Ballast Office for Derry still remains today, as the Quaywest Restaurant, in Boating Club Lane.

Because Malin Head was an important landfall for sailing ships, a pilotage service sprung up around Tremone Bay to service ships bound for Scottish and Irish ports. Pilots on outbound ships, from these ports would have been dropped off at Tremone Bay, on the outbound passage.

Some Scots pilots lodged in homes around Ballyharry to board incoming vessels bound for Scottish ports.

This is reputed to be the reason for the names “Scotch Ballyharry” and “Irish Ballyharry”

The Allan Line is reported to have been the first of the trans-Atlantic shipping companies to “retain” pilots at Tremone to service their ships.

At one stage there would have been 3 types of pilot operating out of Tremone Bay, the traditional “jumpers”, “retained” pilots regularly employed by the Trans-Atlantic shipping lines and “licensed” pilots registered with the Londonderry Harbour Authority.

These men became the basis of the regulated pilotage service for Lough Foyle.

In 1831 there were 29 pilots licensed by Derry Port.

The Masters and Mates of cross-channel steamships which ran into Derry on a regular basis were also licenced by the port to pilot their own ships in and out of port.

In 1854, 30 fully licensed pilots were operating on Lough Foyle. In addition, there were 14 “apprentice” pilots. Some of these were authorised to pilot ships when no licensed pilot could be procured.

In 1899. Pilot boat, “Seagull”, a 26-foot open boat with jib & mainsail, was retained in Tremone. She was registered in the name of James McCann.

In 1854, 1, 038 coasting and 34 overseas vessels were piloted into Derry. Of these, 79 vessels were towed by steam tugs, the rests sailed all the way upriver.

This equates to 2, 144 ship movements under pilotage, for which the pilots were paid £1, 604.

In 2023, there were 616 pilotage movements into and out of Lough Foyle.

144 movements of vessels over 10,000 grt, 23 vessels between 5000-10000 grt and the rest below 5000 grt.

In the absence of internationally agreed regulations for prevention of collisions, the harbour authority had its own regulations for conduct of vessels within its area of responsibility.

The pilot had to carry a copy of these regulations and ship charges on board with him.

Trinity House relinquished its role as the principal pilotage authority, under the Pilotage Act, 1987, and the responsibility for pilotage was passed to individual Competent Harbour Authorities.

The trans-Atlantic Passenger Trade.

The Allan Line started trading between Scotland and Montreal, in 1819. By the 1830s the company had offices in Glasgow, Liverpool and Montreal.

The first Allan Line steamer, the 1,764-ton iron screw “Canadian”, was launched by Wm. Denny and Brothers, of Dumbarton, on July 13,1854 and sailed from Liverpool for Quebec and Montreal on September 16.

By the 1850’s, steamships had started to take over from sail in the trans-Atlantic routes and the number of passengers travelling by steamship, between Ireland and North America increased dramatically during the late 1850s.

The Canadian ports, Montreal and Quebec, on the St Lawrence River, were closed by ice in the winter so the trans-Atlantic services ran into Portland, Maine, Halifax and Boston in winter.

The Galway Line started operations between Galway and New York in 1858 and, in 1859, both the Inman and Cunard Lines introduced calls at Cobh on their routes between Liverpool and New York.

Allan Line

The Allan Lane established a call, off Cobh, on their Liverpool to Portland route. Their first call, off Cobh, was their ship “Nova Scotian” from Liverpool to Portland, on 01 December,1859.

About this time, the port of Derry entered the competition for designation as a mail stop for the Canadian and US mail services. It was pointed out that going North-about, on a Great Circle navigation route, could cut over a day on the voyage.

For the mail services, before the invention of the underwater telegraph cable, time was money, so, on 30 May,1860, the steamers began to call instead at Moville.

The Allan Line announced that, commencing with the sailing of the “North Briton” from Liverpool on July 11, 1860, their steamers would call once a fortnight at Galway and St. John’s on their route between Liverpool, Moville, Quebec and Montreal.

“North Briton”, from Liverpool to Canada, made the first call to Moville. Tender for the call was Capt. Coppins’ “Ardintinney”.

She had 210 passengers on board from Liverpool, 60 more joined from Derry.

However, owing to the intervention of the Canadian Postmaster-General these new arrangements were cancelled. He considered that the number of ports being serviced increased the delivery times for the mail.

The “North Briton” did call off Galway, after leaving Moville, but from then on the mail ship companies continued as before.

They established several drop-off calls around Cape Race and at the mouth of the St Lawrence where urgent telegraphic messages could be passed down to tenders to be taken ashore to local telegraph lines for onward transmission. This could cut delivery times by several days.

Sailings were at fortnightly intervals. by the “Canadian”, the “Indian” and the “Anglo-Saxon”.

On her maiden homeward voyage, the “North American” steamed from Quebec to Liverpool in 11 ½ days, the “Anglo-Saxon” in l0 ½. The “Anglo Saxon’s” second voyage to Liverpool was completed in 9 days and 23 hours.

On a later occasion she reached the Rock Light, Liverpool, from Quebec, in 9 days 5 hours.

It originally took 6 steamers to support the company’s weekly service from Liverpool to Canada, but, in 1885, this number was reduced to 5 – the “Parisian”, “Sardinian”, “Polynesian”, “Sarmatian” and the “Circassian”.

The company announced, in March 1891, that they intended to start a new weekly service between Glasgow, Moville and New York with the “Assyrian”, “Corean”, “Siberian”, “Peruvian” and “Pomeranian”.

Before it could be brought into operation, they purchased the fleet and goodwill of the State Line, which for many years had been running between Glasgow and New York, via Larne, and had recently gone into liquidation.

The New York service was continued under the description “Allan-State Line’, the only change of importance being the substitution of Moville for Larne as the Irish port of call.

At the outbreak of World War 1the Allan Line owned 20 trans-Atlantic steamers. Of these, 3 were sold to the Admiralty and two had been lost by enemy action – the “Hesperian” on September 4, 1915, and the “Carthaginian” on June 14, 1917.

During the war, negotiations took place between the Allan Line and Canadian Pacific shipping company. The deal was kept secret, whether for commercial or military reasons, is unclear, but, at the end of the war, the Canadian Pacific Line took over the remaining 15 Allan Line ships.

After the war, services out of Moville resumed but, by 1923, their offices in Foyle St had closed and they were advertising Belfast to Canada sailings.

The Anchor Line and Anchor – Donaldson Line

The Anchor Line, of Glasgow, ran trans-Atlantic services from Glasgow to New York. They commenced calling into Moville Bay, in 1866.

Anchor Line merged with the Donaldson Line, also of Glasgow, in 1916. Anchor Line ships maintained the Glasgow to Canada service to Quebec & Montreal, in summer, and to Halifax, St John or Portland, in winter, whilst Donaldson Line ships serviced the New York route. Both services called off Moville.

In May 1928, the Anchor Line bought the tender “America” and based her in Derry, renamed “Seamore”. The company then cancelled its contract for tender services with Moville Steamship Co, in 1928.

The “Seamore” was retained as their tender until 1939, when World War 2 brought trans-Atlantic services to an end.

Dominion Line

The Dominion Line, of Liverpool, operated a fortnightly service from Liverpool to Montreal & Quebec, in summer, and to Halifax and Portland, in winter.

Their liners started calling off Moville, in 1887.

The Dominion Line was taken over by White Star Line, in 1902, and their route was changed, replacing Moville with calls off Cobh.

The White Star Line was taken over by Cunard, in 1934.

Trans-Atlantic services during World War 1

The trans-Atlantic trade was discontinued during World War 1. Liners were taken up by the Admiralty for use as Armed Merchant Cruisers, Troop carriers, etc. Their speed was their main defence against U-boats.

Even the cross-channel steamers and the local tenders were taken up for Admiralty use.

Having a U-boat hunting ground on your front door did Derry no favours. Most of the previous Derry coastal trade was shipped across by the shorter routes, like Larne and Bangor.

Emigration from Lough Foyle in the age of steam.

Crop failures and land tenancy issues had created a steady stream of emigrants from Northern Ireland to the new colonies in America and the Caribbean.

Emigrants tend to be pictured as poor peasants fleeing starvation, but many were the younger sons of farmers and businessmen seeking a better life in a new land. These people could afford to pay a reasonable fare for a passage.

There were peaks and troughs in migration streams but, by 1730, the steady stream of emigrants had become a factor in the profitability of Derry sailing ship owners.

English cotton manufacturing was a serious challenge to Irish linen, and this was felt most in the North West. Between 1830 and 1837, 38, 000 people emigrated to America to seek work.

It was during this period that the famous Derry shipowners, like McCorkell’s, Cooke’s, Corscadden, Kelso, etc, started coming to the fore.

Derry businessmen developed the emigration passenger services, under sail, and never really got involved with ocean-going steamships.

The Allan Line initiated the emigration routes from Lough Foyle, in the 1860’s, and other companies followed.

The shortest routes to Canada and North America coupled with British and Canadian mail contracts gave the Foyle a distinct advantage over other Irish ports. Glasgow and Liverpool remained the main emigration ports.

Emigrants from South of a Dublin – Sligo line usually took a cross-channel steamer to Liverpool and emigrated from there, going South, or North, of Ireland depending on cost and destination.

North of the Dublin – Sligo line, the trans-Atlantic mail services supported mail trains which ran from Dundalk to Derry, linking up with lines from Enniskillen, Sligo and West Donegal.

There were 4 railway lines running into Derry quays, including the Londonderry & Lough Swilly Railway system, in Inishowen.

Emigrants could make a short walk from their rail station to the trans-Atlantic tender berth, at the bottom of Bridge Street, to board a tender to Moville.

The offices of the trans-Atlantic liner agents were all situated in the area along the quays, where Foyleside shopping centre now stands.

In 1884, 15, 217 emigrants boarded 154 trans-Atlantic liners at Moville.10, 496 were bound for the USA and 4, 721 were bound for Canada.

Escape to America.

Thomas D’Arcy McGee was the son of a Coastguard, born in Carlingford and raised in Wexford. He became a political activist and edited “The Nation”, the voice of the Young Ireland movement. His involvement in the Irish Confederation and Young Irelander Rebellion of 1848 resulted in a warrant being issued for his arrest.

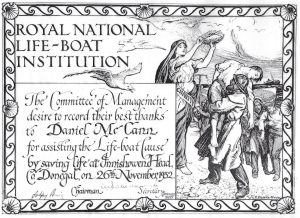

His escape was aided by a Tremone pilot, Roger McCann, who smuggled him onto a ship, outward-bound for America.

In the U S he founded and edited the New York “Nation” and the Boston, “American Celt”, but grew more conservative and emigrated to Canada, where he was elected to the 1st Canadian Parliament, in 1867, as a Liberal-Conservative for Montreal West.

He was assassinated by a Fenian gunman on 07 April 1868.

Elopements

The pilot boat, off Tremone, would have been the last point of contact for departing passengers leaving home forever and farewell letters would have come ashore with the pilot. The first news some parents had of a missing son or daughter would have been a note, delivered from Tremone, announcing their elopement.

Some had more direct announcements. Pilot Charles McCann was leaving an outbound passenger ship, off Ballyharry, when his sister, Grace, appeared at the stern to wave to him. She had eloped with her boyfriend, a McGuinness, of Culdaff.

She was one of the lucky emigrants who were able to come home again. She returned in 1922, on board a trans-Atlantic steamer calling into Moville.

As she was getting ready to board the tender, in Moville Bay, she spotted the Foyle Pilot disembarking. He looked familiar so she asked him was he related to a Charlie McCann, and he replied, “He’s my father” so she replied “Well, I am your Aunt Grace”.

Running down the trans-Atlantic services

After WW1, the Anchor Line resumed trade with only one trans-Atlantic sailing per month. This was increased to 2 sailings, in 1920, and was eventually ramped up to 6 sailings per month.

US emigration laws started to be changed, in1928, and, by 1931, all the exemptions and temporary loopholes had been done away with.

By 1938, only 1 Anchor Line ship per month was calling off Moville.

The Dominion – White Star services ceased using Moville, in 1902.

Pilot Stations

A chart of the Foyle, dated 1833, shows pilot stations at Tremone, Stroove and Greencastle.

The pilot station moved from Tremone Bay to Inishowen Head, around 1884.

The new station was at “The Pound”, to the West of Dunagree Point (Inishowen Lighthouse)

The pilot boat was launched from a beach just below the station.

The watch house for the station was destroyed by Hurricane Debbie, in 1961.

There was a signal Station on Inishowen Head, to service inbound ships. During World War II the Irish Coastwatching Service established a lookout post there. The remains of the house are still visible.

The pilot station was later moved to Port Sallagh, just upriver from the Lighthouse. Date?

The station moved to Carrickarory Pier, Moville, on 01 February 1965. The station was based in Carrickarory / Pier House, now the home of Marie Clarke.

A new pilot station was built on the pier in 1980.

The pilot station moved to its present position, in Greencastle, on 07 September 1999. The station house on Carrickarory Pier is now a holiday home.

“Big” houses on the Foyle

The Griffiths Valuations, 1857, shows several prominent Derry shipowners, Corscaden, Cooke & McCorkell as landowners in prominent sites close to the sea in Stroove. Tenants on these farms maintained a lookout to advise the shipowners of the arrival of their ships off Inishowen Head.

Several of the country lodges along the banks of the Foyle, to seaward of Moville were owned, or leased, by Derry shipowners and businessmen over the years.

Having “tradesmen” as neighbours must really have upset the local landed “gentry”, especially if they were richer.

Rescues at sea

Because the pilot stations were continuously manned, pilots and boatmen were usually amongst the first to learn of boats in distress in the area and the pilot boat crews performed many rescues over the years.

Silver Salvers were presented to Michael O’Donnell and Charlie Cavanagh, Stroove, by Dr Vincent Cavanagh and Tom Gallagher for assistance rendered when their motorboat was in collision with an outbound cattle carrier, in Moville Bay, on 13 July 1969.

At about 0200 on 13 July, Boatmen Michael O’Donnell, Charlie Cavanagh and Frank Loughrey were on duty in the pilot station at Carrickarory Pier.

They had just returned ashore after disembarking pilot, Georgie Hegarty, off the outbound cattle carrier, “Fresian Express”.

A short time later the cattle carrier reported that she had run down a small boat outside Moville Light but could not stop to assist due to the narrow channel and strong tide.

It was salmon season, so the boatmen assumed that it was a boat fishing salmon. Michael and Charlie boarded the pilot boat “Foyle Leader” and proceeded out to rescue the crew of the stricken motorboat. Frank remained in the pilot station to man the VHF radio.

The current was carrying the boat and survivors downriver quickly and it was only by luck that they heard the calls for help. They located the crew and rescued them.

The boat was not a fishing boat but the motor launch “Little Auk”, inbound from Greencastle to Derry. The crew was Tom Gallagher and his brother-in-law, Dr Vincent Cavanagh.

Later that day, they spotted the upturned boat, at Moville Light, drifting inwards on the tide. This time the boatmen took the 2 pilot boats and went out again to try to salvage her.

Towing across the tide caused the boat to sink so the attempt was abandoned. The wreck was eventually brought ashore by Harry Thompson and landed at Moville Pier.

WW2 – Atlantic Star

Inishowen’s prominence as a Western Atlantic landfall made it a busy area during World War I and World War II as Lough Swilly and Lough Foyle were important hubs for convoy escort ships of the Allied navies protecting trade routes passing close by.

The pilot service for Derry continued as usual throughout World War II but with more demands for pilotage services. Pilots were based at Stroove and Derry so that ships coming in and out of Derry had to pick up, or drop off, their pilots in neutral Donegal.

The Foyle pilots were awarded a communal Atlantic Star campaign medal for their services to shipping during the Battle of the Atlantic.

The “Troubles”

On 6 February 1981, a squad of IRA men took over the pilot station and hijacked the pilot boat in an operation to sink the coaster “Nellie M”, anchored in Moville Bay.

The ship was taken over and bombs were placed on board. The ship’s crew was put into the ship’s own lifeboat and towed ashore by the highjacked pilot boat. When the bombs exploded the ship sank in shallow water. She was re-floated in 1982.

On February 23, 1982, a similar operation was carried out by the IRA against the coaster “St Bedan” which was anchored in Moville Bay.

Again, pilot station and pilot boat were taken over and the pilot boat was used to put a bombing party on board the ship. The ship’s crew was towed ashore in their own boat by the pilot boat and the bombs sank the “St Bedan” in deeper water.

The ship was declared a total constructive loss and was raised and scrapped in November 1982.

Pilot losses:

Neil Gillespie, “Nokomis”, 26 January 1884

The “Nokomis” was anchored awaiting a tug to tow her up to Derry when a gale set in, and she dragged anchor.

Pilot, Neil Gillespie, was already on board, awaiting the arrival of the tug.

She was blown over the Tunns and lost off Portstewart. All 16 men on board were lost.

Walter Gillespie, off pilot boat, 22 October 1960

22/10/1960 Walter Gillespie, Shroove.

Drowned whilst coming off “Miramar” on to pilot boat.

Jack McLaughlin, “Esso Colunda”, 19 July 1979

Died after boarding the tanker, in Moville Bay.

Today

Today  Saturday

Saturday